Last Wednesday, a ban was lifted from my WordPress.org account that had been there since sometime in January (or possibly before). I discovered that I was banned on January 6th. I did not receive any communication, any notification, any reason for the block. I assumed it was a mistake.

I wasn’t the only one. Many people got blocked at the same time. The ones I knew about didn’t get any reason either. I will admit that I did not (and still do not) agree with Matt Mullenweg’s public (legal) dispute with WP Engine. Fundamentally, I don’t believe that an organization that maintains some of the most widely used plugins in the WordPress ecosystem can be characterized as “takers”, but I also believe the “maker/taker” argument is fundamentally flawed. (I believe even “takers” can push the ecosystem forward — we wouldn’t know exactly how much WordPress can scale to support massive websites were it not for hosts doing nothing more than running the WordPress software at scale.)

I’ve never felt less like a valued member of the WordPress community than when my account was blocked with no justification.

I immediately reached out to all the relevant channels. I pulled strings within the community that I knew to get my case “escalated”. I asked multiple times for any kind of reason why my account was blocked. Did I say something? Did I do something? As best I can tell, based on conversations I’ve had since, I was blocked for adding a 🤡 (clown face) emoji on one of Matt’s posts in Slack. But no one has explicitly said that to me.

Sidenote: While I acknowledge that that particular emoji became somewhat charged in a way that perhaps made it seem like an attack on Matt’s person, this is one of those things where it’s impossible to understand a person’s perspective without actually having a conversation with them. Because all throughout the COVID epidemic and quarantine period, my partner and I used the 🤡 (clown face) emoji as a reaction to things happening in the world around us. As in “this is wild and unpredictable, it feels like we’re in a circus.” I can’t speak for anyone else who uses the 🤡 (clown face) emoji as a Slack reaction, but for me, it was never intended to mean “Matt Mullenweg is a clown”, it was more “wow, that statement is pretty wild, things are getting out of hand”. I don’t apologize for having opinions. People disagreeing and coming to compromise is part of working and building things in the open.

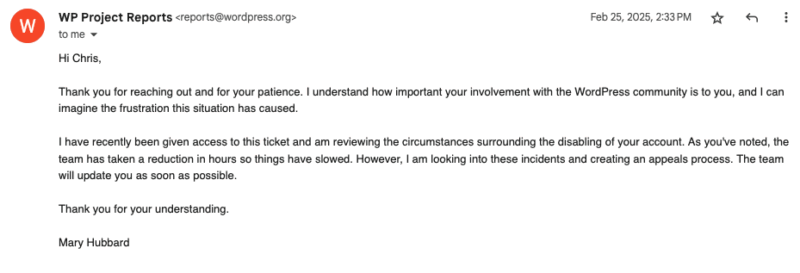

Shortly after I learned I was banned, Automattic announced that it would be scaling back its WordPress contributions. This is notable because, crucially, it is in the hands of Automatticians — namely Matt himself and the (then) newly hired Director of WordPress, Mary Hubbard — to whom escalations such as mine must be manually reviewed by. Given Matt was probably responsible for the ban and Mary was new and just got her WordPress contribution hours scaled back, I doubted a resolution — perhaps ever — given a 40 hour contribution commitment from Automattic as a company. I did, however, finally get a response from Mary after a month and a half.

I sat with it (mostly) in silence. I told people personally, but I didn’t post about it publicly — here or on social media. I was (and am) conscious of the fact that, in my role as Developer Advocate at Pantheon, I am often the face of the company — certainly the face of WordPress at Pantheon. I was afraid of making Pantheon look bad, I was afraid of what effect the ban would have on my role professionally (being the face but also being banned from the community for which you are the face doesn’t seem like a good combination — even while influential community members like Ryan McCue, Joost deValk and Sé Reed had been similarly banned), and I was afraid of drawing even more attention to myself from The Powers That Be by making a public display of my disappointment.

Not posting about being blocked from WordPress.org on my own blog felt like a betrayal to myself and of my own principals. I haven’t always kept this blog up-to-date, but since 2006, I’ve been using WordPress to share my thoughts with the internet. (Seriously. My first post on the WordPress version of this site was from June 2006.) In the nearly 20 years since then, I’ve shared about my first WordCamp, my first WordPress job, when I joined Human Made — basically, my entire WordPress life has largely been documented on this blog. And that life extends over a long time of being deeply involved in the community. Not talking about something that serious and impactful really bothered me. And I fought with myself over it many times.

How the bans affected WordPress security

In March, Patchstack ran a “bug bounty boost”, and informed plugin developers who have registered plugins in their Vulnerability Disclosure Program that they might be getting notifications of vulnerability disclosures. I joined the program a couple years ago, so I wasn’t surprised when my Progress Bar plugin (probably the oldest plugin I still maintain) received a vulnerability disclosure. The problem was, I couldn’t do anything about it. Even if I fixed the issue, I could only push the change up to GitHub. Being blocked from WordPress.org meant I had no way of submitting the patched version to the WordPress repository where the 1000+ users are likely to have downloaded it from.

In the preceding months, I found myself reevaluating the plugins that I maintain on WordPress.org, those that are on GitHub and how I want to continue to distribute them. I haven’t actively pushed to any of my .org plugins in a long time and the majority of my plugins are things that seemed like a fun idea at the time but were mostly self-serving plugins to solve a need that I had. I went through my GitHub repositories, archived a bunch of projects and pushed others to Packagist so that they could be installed via Composer instead. This vulnerability disclosure validated that decision (anyone who happened to have the plugin installed via composer require jazzsequence/progress-bar would be able to get the updated fix), but it made me realize the real consequences of blocking WordPress community contributors from the WordPress repository. I was now responsible for a vulnerability in WordPress. And I couldn’t fix it.

And then I thought about the precedent set by Matt several months earlier, when he assumed ownership of WP Engine-owned plugin Advanced Custom Fields over a disclosed (minor) vulnerability. Because they were locked out, they were unable to push a fix, and Matt decided that that was enough reason to seize the plugin and use an internal contributor team to push out the fix — and later a full rebrand, Secure Custom Fields (Advanced Custom Fields has since been returned to WP Engine at the request of a court-issued injunction). I’m not WP Engine, but the question lingered — if Matt wanted to, could he just take my plugin(s) from me in the name of maintaining platform security? I mean, the answer is yes, he could, even if the reality was, in this case, he likely wouldn’t.

How the ban affected my sense of community

I’ve criticized choices made by WordPress core development (and Matt Mullenweg in his leadership capacity of the project), but I’ve never felt less like a valued member of the WordPress community than when my account was blocked with no justification. Even as many of my former colleagues and friends have moved away from WordPress, I never saw myself doing that…until I was banned. What it told me was that, despite having a .org account for 17 years, despite using WordPress for close to 20, despite giving presentations, writing plugins, creating online training, getting contributor credits, living and breathing WordPress for close to two decades, I was no longer considered a valuable member of the community.

And that’s when I went to DrupalCon Atlanta.

And I saw this when I got there.

I realized that it was almost luck that brought me to WordPress and given a slightly different set of circumstances or a different decision, I could have swapped WordPress for Drupal. I realized that a lot of the problems and challenges in the WordPress ecosystem are shared by the Drupal community — and several of those challenges have been addressed by slightly different decisions along the way. I realized that the people that make up the two developer communities are largely similar. But, at least for the moment, the Drupal community seemed a whole lot more welcoming. I was fairly certain that my Drupal.org account would not be disabled because of an emoji. And I was welcomed on (and invited back to…spoilers) the prominent Talking Drupal podcast.

I’m thankful that PressConf happened when it did, because it revitalized my sense of community within WordPress. It made me feel like I was a part of the community even if I was maybe on the outside. And it gave me an opportunity to commiserate with others who were in similar situations. I wasn’t the only one checking the WordPress.org login daily since Matt’s declared Jubilee.

I believe now more than ever that WordPress people need to go to DrupalCon or, barring that, we at least need to talk to each other more. A lot more. Because we’re not alone over here (whatever “here” means to you). And collaboration is far more productive than competition. In the WordPress ecosystem, we compete over a lot of things that the Drupal community just doesn’t, and I don’t always think that’s a net benefit. If the result of those conversations is more shared ideas or developers hopping from one ecosystem to the other, I think that would be a positive effect.

More than anything else, though, as jaded as I may have felt before being banned, existing in a weird limbo of inside-but-outside the WordPress community for months made me question whether it was worth it, whether this is something that is still for me. And, to be honest, I’m still experiencing a bit of whiplash from being reinstated (along with 31 others) last week (also with no communication or fanfare). I’m relieved, but what does it actually mean? I still don’t know. I’m not sure I’ll ever know. But I’m still here, so that’s a start.

[image credit: Andy Fragen]

Leave a Reply