RPM2011 is 9 days away and it seems appropriate to finish this retrospective series before RPM starts. Part 1 of this series covered the early beginnings of my interest in music up through high school and eventually turning to the computer as a means for producing and recording music. Part 2 will cover how that evolved and changed in college and the upcoming third and final part will cover everything that happened between graduating college and now. Ready? Go.

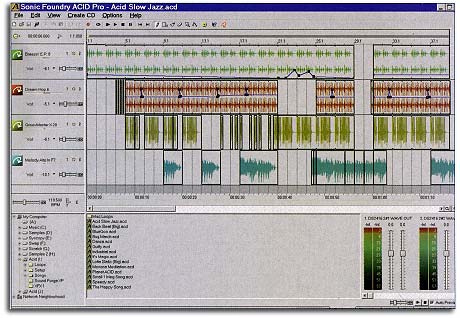

Last week I talked about Sweet Sixteen and how that helped me create music in ways I hadn’t tried before. I gave up trying to create punk rock and metal with my cheap keyboards and started making more electronic-based goth and industrial. The end of high school and beginning of college marked the sudden rise of electronica into the mainstream with artists like Underworld, The Prodigy, Sneaker Pimps, Chemical Brothers, Crystal Method, Moby, Portishead and Fatboy Slim all bringing their diverse takes on dance music and suddenly it was all over the radio. Along with that shift in popular music came a shift in music-making technology. I began to use (mostly unsuccessfully) Cakewalk for music-making, but was frustrated by the complete lack of intuitiveness. On the other hand, I got a taste of Sonic Foundry Acid and was hooked. Acid was based on loops, and in about 15 minutes (with the right bundle of samples) you could create a danceable track along the lines of what The Chemical Brothers and Fatboy Slim were making money from. In many ways it was empowering, and in many ways it killed electronic music by making it too easy.

Last week I talked about Sweet Sixteen and how that helped me create music in ways I hadn’t tried before. I gave up trying to create punk rock and metal with my cheap keyboards and started making more electronic-based goth and industrial. The end of high school and beginning of college marked the sudden rise of electronica into the mainstream with artists like Underworld, The Prodigy, Sneaker Pimps, Chemical Brothers, Crystal Method, Moby, Portishead and Fatboy Slim all bringing their diverse takes on dance music and suddenly it was all over the radio. Along with that shift in popular music came a shift in music-making technology. I began to use (mostly unsuccessfully) Cakewalk for music-making, but was frustrated by the complete lack of intuitiveness. On the other hand, I got a taste of Sonic Foundry Acid and was hooked. Acid was based on loops, and in about 15 minutes (with the right bundle of samples) you could create a danceable track along the lines of what The Chemical Brothers and Fatboy Slim were making money from. In many ways it was empowering, and in many ways it killed electronic music by making it too easy.

Fœtus Kryste – 17, 18, 19

The problem with Acid was that it was entirely based on loops and contained no tools for actually creating any of those loops. So you needed another program to actually create the loops if you didn’t want everything you did to be derivative or based off loops and samples found on the web (unless you could create your own loops with live instruments). Sometime after I found Acid, I found FruityLoops (and later, its companion, FruityTracks which eventually just got integrated into the same package). FruityLoops was a essentially software beatbox that came bundled with various drum and instrument samples that you could use to create beats and patterns. Combined with FruityTracks, you could assemble those into full compositions.

The problem with Acid was that it was entirely based on loops and contained no tools for actually creating any of those loops. So you needed another program to actually create the loops if you didn’t want everything you did to be derivative or based off loops and samples found on the web (unless you could create your own loops with live instruments). Sometime after I found Acid, I found FruityLoops (and later, its companion, FruityTracks which eventually just got integrated into the same package). FruityLoops was a essentially software beatbox that came bundled with various drum and instrument samples that you could use to create beats and patterns. Combined with FruityTracks, you could assemble those into full compositions.

Fœtus Kryste – Spacegirl

Despite having these new tools, I look back on those years of writing music and realize I was floundering; hopping from one program to the next and never being comfortable in any of them. It wasn’t until I took a class in the Music department on early electronic music that I began to abandon conventions and, in so doing, begin to find my voice (or sound). To be honest, I didn’t know there was electronic music before Kraftwerk, really, so learning about a history that dated as far back as the 1940s was far from boring, and I was enthralled by the music of artists like Steve Reich, Alvin Lucier, Charles Dodge and Morton Subotnick. My two compositions for the class show both my influence from sample-based music as well as my new-found love of twiddling knobs on the decades-old analogue synthesizers in the music department. It was also in this class that I had my first experience with “real” recording software, namely Cubase and ProTools, running on an old Macintosh with only a monochrome monitor.

Fœtus Kryste – Untitled #1 & Untitled #2

Chris Reynolds – Experiment on Indian Raga

The next semester I went abroad to England where I continued doing more or less what I’d been doing until I heard the score for a stage adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s VALIS by my friend (and former roommate) Tess Tanen. The writer/director, Rob, had asked both of us if we’d be interested in participating but I couldn’t because I’d be across the pond. Nonetheless, I was anxious to be involved and hearing Tess’s score inspired me. Being in England, I was immersed in DJ culture, discovered underground UK Garage and drum & bass, and was DJ’ing on the University’s radio station and occasionally at a club run by a group of the students. At the same time I was immersed in the local goth scene. In the UK, goth had closer ties to metal and — simultaneously — electronica, and there wasn’t the sort of hard defined boundaries between different sub-sub-cultures like I saw at home. It was perfectly normal for someone to be heavily into “cybergoth” — listening to ATB, Paul VanDyk and Paul Oakenfold — to get tickets to see Iron Maiden at Wembley Stadium. So, it was through these influences that the VALIS Remix Album came to be. I was very interested in creating a unique sound that was a combination of various musical influences and styles which included hip-hop, electronic music, and experimental music.

The next semester I went abroad to England where I continued doing more or less what I’d been doing until I heard the score for a stage adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s VALIS by my friend (and former roommate) Tess Tanen. The writer/director, Rob, had asked both of us if we’d be interested in participating but I couldn’t because I’d be across the pond. Nonetheless, I was anxious to be involved and hearing Tess’s score inspired me. Being in England, I was immersed in DJ culture, discovered underground UK Garage and drum & bass, and was DJ’ing on the University’s radio station and occasionally at a club run by a group of the students. At the same time I was immersed in the local goth scene. In the UK, goth had closer ties to metal and — simultaneously — electronica, and there wasn’t the sort of hard defined boundaries between different sub-sub-cultures like I saw at home. It was perfectly normal for someone to be heavily into “cybergoth” — listening to ATB, Paul VanDyk and Paul Oakenfold — to get tickets to see Iron Maiden at Wembley Stadium. So, it was through these influences that the VALIS Remix Album came to be. I was very interested in creating a unique sound that was a combination of various musical influences and styles which included hip-hop, electronic music, and experimental music.

c.s.reynolds – Serpentine

Eventually though, I gave up trying to use just about anything for composition in favor of SoundForge, an advanced recording program from the same company the created Acid (which was later acquired by Sony) with various effects filters to stretch, shrink, mutilate and destroy any sound you could create. Using SoundForge, I began my journey into experimental music, duplicating many of the experiments of those early avant-garde experimental composers. I created interpretations of Alvin Lucier’s “I am sitting in a room” of Steve Reich’s phase patterns, of Harold Budd‘s “Candy-Apple Revision” (whose instructions are simply play something in D-flat major). These experimentations were reinforced by another class taught again by the same professor who did the electronic music class specifically on Experimental Music. I wrote an experimental piece called “Music by Computers” which was a page of binary (0s and 1s) in random order and the instructions were to interpret however you liked (I have three recorded variations on the “Music by Computers” — one by the Experimental Music Ensemble, which was made up of the students of the class, one by The Loafmen, and one I recorded later in which I transcribed the binary into alphanumeric characters and used those to determine the notes and rests and key and time changes). It was during this time that I was probably the most prolific, although part of that was influenced by the fact that the experiments were often lengthy ordeals. Indeterminacy became my guide, and I became fascinated with an approach to music that was spontaneous, random and evolving, which is still infused in the music I make now.

It was also during this time that I was commissioned to write music for a stage adaptation of William Blake’s “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” which I also had a part in.

c.s.reynolds – Beyond Heaven + Hell

And then there was The Loafmen. There were four of us, myself included, in the Experimental Music class plus one other person — the previously mentioned Rob, a former student. Rob, Peter, Tess and I were all in Rob’s car listening to something in Rob’s vast post-rock collection (most likely Don Caballero), when one of us said “we should start a band”. This didn’t actually sound half-bad so we recruited Crissy, another student in the class who played drums, and became The Loafmen (named after the “loaves of squeaking viscera” in a rubber skeleton toy that Crissy had). The Loafmen were part performance art, part experimental music, and part post-rock and truly a product of the ideas we were immersing ourselves in inside and outside the Experimental Music class. This, in turn, had an effect on the types of things I was experimenting with and what I was experimenting with had an effect on what I brought to The Loafmen. The Loafmen had four rules:

Don’t talk about what we’re going to play before we play it

Don’t talk about what we’re going to play before we play it- Listen to what the other members are doing

- The song ends when it ends

- Everyone is a Loafman unless they aren’t alive or capable of falling down

Forgoing expensive (or even less-expensive) studio equipment, all of The Loafmen’s music was recored by a single VHS camera I got on eBay for the film I was making for my senior project. Initially, it was just the easiest thing on-hand, but eventually it became part of the process. We’d rehearse for several hours, then go back to my room to watch the results. We were a bit like guerilla artists, taking over the common room for our rehearsals and using found objects as instruments, and the videos were a way to sort of document the visual aspect of The Loafmen. (I still have the tapes and plan to digitize them at some point. They kind of need to go on YouTube.) In addition, it was generally through watching the tapes that we came up with the song titles for what we had recorded.

At the end of the semester we did two performances, one for the Experimental Music class and one in a student-run coffee house built into the basement of one of our dorms. The latter was called the “Milk and Cookies show” and we provided milk and cookies to anyone who came to see us (obviously). In addition, at a large-scale rave that a student organized as his senior project (what can I say, our school was awesome), I did a live DJ performance of the experimental pieces I had been working on myself, called Fractal.

c.s.reynolds – Fractal

The experimentation continued and eventually evolved into completely new styles, but that will have to wait for Part 3…

Leave a Reply